In the late 1980s, while still a university student, I visited the newly established Volkswagen joint venture in China as part of an enrichment programme. At the time, it was one of the very first examples of foreign car production in China. I remember being struck by the novelty of seeing a modern car plant in operation — though back then, car ownership remained a luxury for the few.

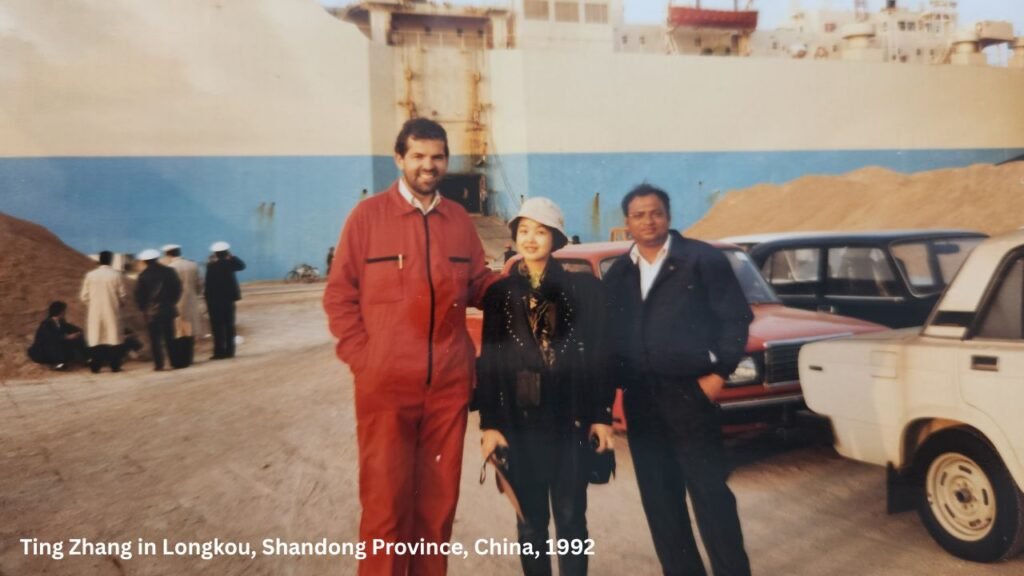

A few years later, in 1992, I stood at Longkou Port in Shandong Province, receiving 1,400 Lada cars from Russia. That shipment was destined for China’s taxi market at a time when domestic passenger car brands were virtually non-existent. From those early beginnings, I could not have imagined just how far — and how fast — the Chinese automotive industry would travel.

Fast forward three decades, and I was recently invited to share my perspective with Russell Padmore on the BBC World Service, reflecting on the extraordinary transformation of the industry — and in particular, the global rise of Chinese electric vehicle (EV) manufacturers.

State Policy Meets Market Ambition

China’s auto revolution has never been accidental. It has been driven by:

- Strong state support — through the “Made in China 2025” strategy, subsidies, and tax incentives. I explored how this wider policy environment has impacted Western firms in my earlier piece Business in China 2025: What’s Really Changed for Western Companies.

- Industrial partnerships — fostering domestic champions like BYD, Geely, and Chery, while linking them to global players such as Volvo, Polestar, GM, and VW.

- Infrastructure and ecosystems — from battery giants like CATL to dealer networks and after-sales service in overseas markets.

This policy-market fusion enabled China to overtake Japan in 2023 as the world’s largest vehicle exporter, with EVs at the heart of that story.

Going Global: Ambition Without Borders

Chinese automakers are entering overseas markets with remarkable speed. Consider:

- Direct exports: BYD even built its own shipping fleet to overcome bottlenecks.

- Local manufacturing: BYD in Hungary, Chery in Brazil, Geely in Europe.

- Brand building: I saw their impressive presence first-hand at the Goodwood Festival of Speed.

Inside BYD: A Glimpse of the Future

When I visited BYD’s headquarters showroom in Shenzhen, I saw first-hand the factors behind their global success:

- Vertical integration — BYD controls the supply chain from batteries to semiconductors, a unique advantage in cost and resilience.

- Fast-paced innovation — new models are launched at remarkable speed, with futuristic functions like the U8’s drone capability. I wrote more broadly about these innovation trends and the scope for UK–China collaboration in Driving Innovation Trends in China’s EV Sector and UK Partnership Opportunities.

- Global outlook — the showroom was buzzing with both domestic and international visitors, underscoring BYD’s openness to collaboration.

What struck me most was not just technology, but a culture of adaptability and ambition.

Price, Technology, and Value for Money

Much of the discussion around Chinese EVs focuses on their pricing advantage, but the full picture is more nuanced.

Yes, Chinese EVs often undercut Western rivals by 20–30%. This is enabled by vertical integration and domestic supply chains — particularly in batteries, where companies like CATL and BYD dominate. With fewer layers of outsourcing, they cut costs while keeping tighter quality control.

But value for money is not only about price. Many Chinese models now pack in technology and features that would cost a premium elsewhere:

- Battery innovation — longer ranges, faster charging, safer chemistries.

- Digital experience — rotating touchscreens, AI-powered voice navigation, seamless smartphone integration.

- Design and comfort — stylish interiors, advanced infotainment, and trim levels that feel more premium than their price suggests.

This is a powerful formula: affordability + innovation + user experience. It allows Chinese automakers to appeal not only to cost-sensitive buyers but also to younger, tech-savvy consumers who want the latest features without the premium price tag.

In other words, China’s EVs don’t just compete on cost — they increasingly compete on desirability.

The Question of Trust

In my BBC interview, one issue we discussed was recalls. Of course, recalls are a concern — but they are not unique to Chinese brands. Ford, Tesla, and Hyundai have faced similar challenges. What matters is how quickly and effectively problems are resolved.

Trust is fragile. For Chinese brands, which are still new in Europe and the U.S., it is vital. In many cases, they are going the extra mile to ensure export quality, knowing the stakes are high.

Facilitating UK–China Automotive Collaboration

My own career has given me a front-row seat to these changes. In the mid-2000s, I helped Great Wall Motors partner with a Cambridge-based automotive design firm, one of their early steps towards internationalisation. Today, Great Wall has grown into one of China’s major players, illustrating how cross-border collaboration has shaped the sector’s development.

From Lada Imports to BYD Exports: A Transformation in Scale

When I helped bring in those Ladas through Longkou in the early 1990s, China’s auto sector was embryonic. By 2009, China had become the world’s largest auto market. Today, it produces more than 21 million passenger vehicles annually, exports more than 5 million units, and leads the global EV race.

It has been remarkable to witness this journey — from a nation dependent on imports to a powerhouse setting the pace in the most disruptive sector of global mobility.

Looking Ahead

The road forward is not without obstacles:

- Geopolitical tensions will test the resilience of global expansion.

- Brand perception and trust must be carefully nurtured.

- Value for money will remain the core differentiator.

One more point stands out: the relationship between Western and Chinese automakers will increasingly be one of co-opetition — a blend of competition and cooperation. They compete fiercely on technology and price, but also collaborate through joint ventures, supply chains, and shared innovation.

For me, having witnessed this evolution from the VW joint venture of the 1980s, to the Lada imports of the 1990s, to today’s EV champions, one thing is clear: the story of China’s auto industry is no longer about “catching up.” It’s about shaping the future of mobility worldwide.